Restrictions on religion around the world continued to climb in 2016, according to Pew Research Center’s ninth annual study of global restrictions on religion. This marks the second year in a row of increases in the overall level of restrictions imposed either by governments or by private actors (groups and individuals) in the 198 countries examined in the study.

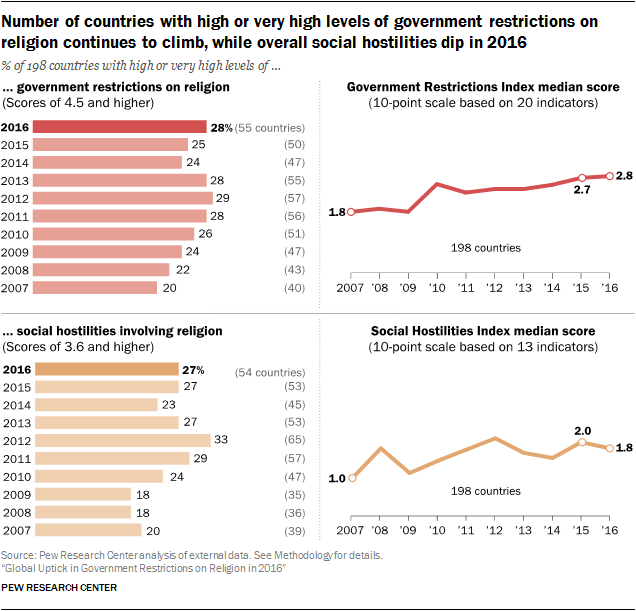

The share of countries with “high” or “very high” levels of government restrictions – that is, laws, policies and actions by officials that restrict religious beliefs and practices – rose from 25% in 2015 to 28% in 2016. This is the largest percentage of countries to have high or very high levels of government restrictions since 2013, and falls just below the 10-year peak of 29% in 2012.

Meanwhile, the share of countries with “high” or “very high” levels of social hostilities involving religion – that is, acts of religious hostility by private individuals, organizations or groups in society – remained stable in 2016 at 27%. Like government restrictions, social hostilities also peaked in 2012, particularly in the Middle East-North Africa region, which was still feeling the effects of the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings. The number of countries with high or very high levels of social hostilities declined in 2013 and has remained at about the same level since, but it is higher than it was during the baseline year of this study (2007).

In total in 2016, 83 countries (42%) had high or very high levels of overall restrictions on religion – whether resulting from government actions or from hostile acts by private individuals, organizations and social groups – up from 80 (40%) in 2015 and 58 (29%) in 2007.1

At the same time, most countries in the world continued to have low to moderate levels of religious restrictions. Looking separately at the global median scores on the Government Restrictions Index (a 10-point scale based on 20 indicators of government restrictions on religion) and the Social Hostilities Index (a 10-point scale based on 13 measures of social hostilities involving religion) offers a mixed picture of how religious restrictions are changing. In 2016, the global median score on the Government Restrictions Index ticked upward, from 2.7 to 2.8, while the median score on the Social Hostilities Index fell slightly, from 2.0 to 1.8.

In many countries, restrictions on religion resulted from actions taken by government officials, social groups or individuals espousing nationalist positions. Typically, these nationalist groups or individuals were seeking to curtail immigration of religious and ethnic minorities, or were calling for efforts to suppress or even eliminate a particular religious group, in the name of defending a dominant ethnic or religious group they described as threatened or under attack. In the Netherlands, for instance, Geert Wilders’ Freedom Party announced an election platform in 2016 that called for the “de-Islamization” of the country, including barring asylum seekers from Islamic countries, prohibiting Muslim women from wearing headscarves in public, closing all mosques and banning the Quran.2 In another case, the Czech group Block Against Islam (which opposes allowing Muslim refugees into the country and calls for restrictions on the Muslim community) organized about 20 anti-Islam rallies around the country during the year.3

More broadly, 2016 saw an uptick in nationalist activities around the globe that are reflected in elements of both the Government Restrictions Index (GRI) and the Social Hostilities Index (SHI).4

Nationalist political parties aim rhetoric at religious groups

Government actors – whether political parties or individual public officials – at times used nationalist, and often anti-immigrant or anti-minority, rhetoric to target religious groups in their countries in 2016. About one-in-ten (11%) countries had government actors that used this type of rhetoric.5 This marks an uptick from 2015, when 6% of cases involved political parties or officials that espoused nationalist views.6

This phenomenon was especially common in Europe. About a third of European countries (33%) had nationalist parties that made political statements against religious minorities, an increase from 20% of countries in 2015.7 In France, for example, Marine Le Pen, leader of the National Front, promised to continue the ban on religious clothing and symbols in public places specifically to “fight the advance of political Islam.”8

In the Asia-Pacific region, nationalist political parties targeting religious groups were found in a smaller share of countries (12%), including Burma (Myanmar), India and New Zealand. For example, Winston Peters, leader of the New Zealand First Party, said in June 2016 that certain countries “treat their women like cattle,” and he suggested that all immigrants should be screened for unacceptable attitudes before being permitted to enter the country.9 Some media reports said he specifically referred to Muslim immigrants, which he denied.10

Overall, Muslims were the most common target of harassment by nationalist political parties or officials in 2016, typically in the form of derogatory statements or adverse policies. This was the case in Denmark, where the Danish People’s Party (DPP) backed a measure passed by the city council in Randers that made “traditional” meals – including pork products – mandatory in public institutions, including schools. Martin Henriksen, a spokesperson for the DPP, said the bill would preserve Danish culture and that the party was “fighting against Islamic rules and misguided considerations dictating what Danish children should eat.” The bill was opposed by members of the Muslim community because they saw it as stigmatizing; Muslims traditionally do not eat pork.11

In the United States, Muslims were the targets of derogatory rhetoric and proposed discrimination. In July, Republican presidential nominee Donald J. Trump criticized the parents of a Muslim soldier who was killed in Iraq, saying the soldier’s mother was not “allowed” to speak at the Democratic National Convention, despite being on stage with her husband, implying that this was a result of her religion.12 Later in the year, President-elect Trump appeared to stand by plans for a temporary ban on Muslim immigration to the United States and a proposed requirement that U.S. Muslims register in a database.13

Nationalist parties also singled out Jews, Christians and members of other minority faiths. In Bulgaria, Jehovah’s Witnesses reported an ongoing campaign against their religion by two nationalist parties, the National Front for the Salvation of Bulgaria and the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, which together form the Patriotic Front political alliance in the country’s legislature.14 And, in Sweden, representatives of the Sweden Democrats Party made anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim remarks on multiple occasions during the year.15

Nationalist organizations targeted religious minorities as well

Nationalist ideologies were not limited to governments. The number of countries where nongovernmental nationalist organizations (as opposed to governmental actors, such as officeholders or political parties with a role in government) targeted religious groups also increased in 2016.

One of the 13 measures that comprise the Social Hostilities Index is whether any organized group or groups “sought to dominate public life with their perspective on religion” at the expense of other religious groups. Like the other SHI measures, the answer to this question has been coded annually for each country, based on the same set of publicly available sources (for more details, see the Methodology and SHI Question 7 in Appendix D).

In 2016, the study found 77 countries where organized groups sought to dominate public life at the expense of certain religions, up from 72 countries in 2015. Not all of these groups were nationalist or espoused positions against immigrants and religious minorities, but the number of groups that did espouse these positions also rose, from 27 countries in 2015 to 32 in 2016.

The majority of social groups displaying this kind of nationalist or anti-immigrant and anti-minority activity – 25 out of the 32 – were in European countries, including the United Kingdom, Ireland and Hungary. A few additional countries with these types of groups were in the Asia-Pacific region, including Sri Lanka, India and Australia.

In Australia, for example, nationalist groups and local residents opposed the building of a mosque in southeast Melbourne; eventually a local council denied approval for its construction. Additionally, in May and July 2016, police made arrests in Melbourne after violence broke out between religious freedom advocates and opponents of Islam at competing protests.16

This type of activity was common among countries in this category: Religious minorities were often the targets of demonstrations, derogatory public comments or violent acts by nationalist groups. In all 32 countries where nationalist groups sought to dominate public life in 2016, they targeted religious minorities, such as Muslims, Jews, minority Christian churches or members of other faiths.

In European countries, Muslims were targeted most frequently. Muslims were the focus of nationalist groups in 20 of the 25 European countries where these types of groups were active. Following the terrorist attacks in Brussels in March 2016, for example, the Spanish nationalist group Madrid Social Home hung signs near a major mosque in Madrid reading “Today Brussels, tomorrow Madrid?” and posted “Mosques out of Europe” on Twitter.17

But while Muslims were the primary target of nationalist movements across the globe, Jews, Christians (including Jehovah’s Witnesses) and others were targeted as well. For example, in 2016 nationalist groups aimed activities against religious groups in three countries in the Americas – Brazil, Peru and the United States – and Jews were a target in all three; in addition, Muslims also were targeted in the U.S.

Neo-Nazis continued to use anti-Semitic language and engage in online harassment of Jewish journalists in the U.S.18 And the Andean National Socialist Movement of Peru continued to deny that the Holocaust occurred, sell anti-Semitic literature and DVDs, and call for the expulsion of the Jewish community from Peru.19

Nationalist groups and parties gain standing in 2016

Nationalism was certainly not a novel ideology in 2016; nationalist political parties and organizations have been active around the world for centuries. But some nationalist political parties did gain more support in various ways in 2016. In addition to Rodrigo Duterte’s election in the Philippines, support in the polls for Marine Le Pen of the National Front party increased leading up to the 2017 French presidential election (which Le Pen ultimately lost in a runoff to Emmanuel Macron). And the Alternative for Germany party, a German far-right nationalist party, some branches of which have called for a ban on the construction and operation of mosques, won a significant number of seats in three state parliament elections in 2016 (before gaining seats in the national parliament in 2017).20

Nationalist organizations in society at large were also not a new phenomenon in most of the countries where they were active in 2016, but some spread their operations to new locales during the year. For instance, Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the West established an Irish branch in 2016 – a move that was met with protests by groups describing themselves as opposing racism and supporting immigrants.21 And a Finland-based group called Soldiers of Odin spread in 2016 to multiple cities in Finland and some neighboring countries, including Estonia, organizing marches against “Islamist intruders” and vowing to set up volunteer street patrols to counter crime by migrants.22

In India, some Hindu nationalists formed “cow protection” groups that viewed cow slaughter and eating beef as an affront to Hindu deities that represent motherhood. These groups have existed in prior years in India, but they increased their activities in 2016. Members of these groups violently confronted consumers of beef or those they believed may have been involved in slaughtering beef, in many instances harassing and in some cases beating or killing their targets.23

About this report

This is the ninth in a series of reports by Pew Research Center analyzing the extent to which governments and societies around the world impinge on religious beliefs and practices. The studies are part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world. The project is jointly funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation.

To measure global restrictions on religion in 2016 – the most recent year for which data are available – the study ranks 198 countries and territories by their levels of government restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving religion. The new study is based on the same 10-point indexes used in the previous studies.

- The Government Restrictions Index measures government laws, policies and actions that restrict religious beliefs and practices. The GRI comprises 20 measures of restrictions, including efforts by government to ban particular faiths, prohibit conversion, limit preaching or give preferential treatment to one or more religious groups.

- The Social Hostilities Index measures acts of religious hostility by private individuals, organizations or groups in society. This includes religion-related armed conflict or terrorism, mob or sectarian violence, harassment over attire for religious reasons, or other religion-related intimidation or abuse. The SHI includes 13 measures of social hostilities.

To track these indicators of government restrictions and social hostilities, researchers combed through more than a dozen publicly available, widely cited sources of information, including the U.S. State Department’s annual reports on international religious freedom and annual reports from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, as well as reports from a variety of European and UN bodies and several independent, nongovernmental organizations. (See Methodology for more details on sources used in the study.)

Religious restrictions vary by region, religious group

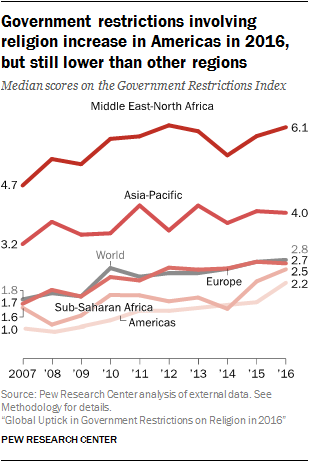

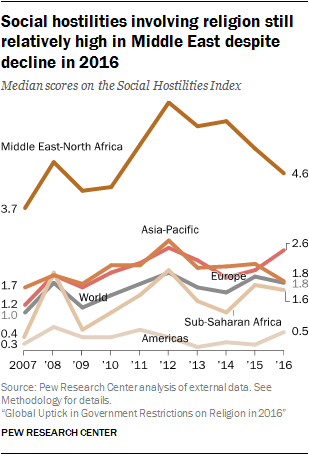

The Middle East-North Africa region continued to have the highest median level of government restrictions on religion in 2016, although the Americas had the sharpest increase in its median score, rising from 1.7 in 2015 to 2.2 in 2016. The rise in the Americas’ median score was partly due to incidents in which worship or proselytizing were restricted. For example, in Paraguay, police forcibly evicted the Ava Guarani indigenous community from their ancestral lands, demolishing homes, schools and places of worship.24 And in Mexico, Jehovah’s Witnesses were prohibited from proselytizing by the municipal authority in San Jorge Nuchita.25

Meanwhile, Europe and the Americas were the only regions to experience increases in median levels of social hostilities involving religion, with Europe seeing the sharpest increase. The Middle East-North Africa region continued to experience a decline in its median score, although it remained the region with the highest levels of social hostilities.

When combining measures of government restrictions and social hostilities, more than four-in-ten countries (42%) had high or very high levels of overall religious restrictions in 2016. Since some of these countries are among the world’s most populous (such as China and India), this means that a large share of the world’s population in 2016 – 83% – lived in countries with high or very high religious restrictions (up from 79% in 2015). It is important to note, however, that these restrictions and hostilities do not necessarily affect the religious groups and citizens of these countries equally, as certain groups or individuals – especially religious minorities – may be targeted more frequently by these policies and actions than others. Thus, the actual proportion of the world’s population that is affected by high levels of religious restrictions may be considerably lower than 85%.

The analysis also finds that among the world’s 25 most populous countries, Egypt, Russia, India, Indonesia and Turkey had the highest overall levels of government restrictions and social hostilities in 2016. China had the highest score on the Government Restrictions Index, while India had the highest score on the Social Hostilities Index.

Looking at religious groups, harassment of members of the world’s two largest groups – Christians and Muslims – by governments and social groups continued to be widespread around the world, with both experiencing sharp increases in the number of countries where they were harassed in 2016. There was also a jump in the number of countries where Jews were harassed in 2016 following a small decrease in 2015.